The following sermon was preached on Ash Wednesday, March 5, 2014 at Good Shepherd Community Church in Scarborough. The Scripture readings were Genesis 3:17-19; 1 John 1:5-10; Luke 18:9-14.

I sometimes warn my theology students about the dangers of using video clips in sermons. The rich, multi-sensory experience of watching a video can easily threaten to overwhelm the unadorned words that are merely spoken by the preacher. Yet, in spite of my own better judgement, I have gone and shown what is widely regarded to be one of the most compelling music videos ever made. The video based upon Johnny Cash’s version of the Nine Inch Nails song “Hurt” is undeniably a courageous and profoundly moving artistic work. By showing it to you directly before my sermon, I am running the distinct risk that you will go from this place tonight remembering nothing of what I’ve said, but instead will find your imaginations captured by the powerful words and haunting images of the video you have just seen. Now that might not necessarily be a bad thing, because the video does resonates in a profound way with the description of human existence we encountered in our reading from Genesis, which spoke of “painful toil,” “thorns and thistles” and finished with the declaration, “for dust you are and to dust you will return.”

The video for “Hurt” derives much of its power from the provocative juxtaposition of images and of images with words. The most noticeable of these juxtapositions involves the contrast between the images of the young Johnny Cash, a superstar exuding vitality and charisma, with the figure of the frail and fragile Cash in his last years. In one frame we see the young country-music phenom commanding the attention of a sold-out audience. In another we see an elderly man, pouring out a glass of wine, his hand visibly trembling from the neurological disorder that afflicts his body. The line from the chorus, “You could have it all, my empire of dirt” is strikingly juxtaposed with images from the House of Cash, a museum filled with Cash’s most precious memorabilia and awards collected over the course of his career. In the video we see that the House of Cash sits in a dilapidated state, permanently closed to all visitors. Johnny’s wife, June Carter Cash, looks worriedly down upon him as he sings, “everyone one I know goes away in the end,” perhaps even at this point knowing that she herself would soon face death and leave her husband alone. But the hurt at the center of the song does not simply arise on account of our status as finite creatures destined to suffer the ravages of time and to experience the tragedy of separation. It is also, perhaps even primarily, attributable to the painful reality that we are creatures ravaged by sin, destined to die under a curse. In the second verse, Cash sings, “I wear this crown of thorns / upon my liar’s chair / full of broken thoughts / I cannot repair.” He acknowledges that he has been complicit in wrongs that he cannot make right. There is something wrong, not only in the world, but ultimately in his very soul. Hence the haunting refrain found at the end of the chorus, “I will let you down, I will make you hurt.” I have recently finished reading the new Johnny Cash biography written by Robert Hilburn.1 In the biography it becomes painfully apparent how much Cash did let down and hurt the ones he loved over the course of his life.

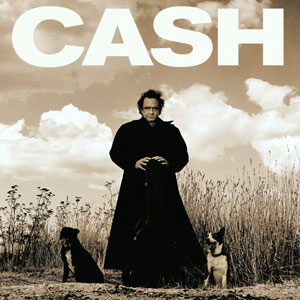

Another juxtaposition that emerges clearly in the biography is the juxtaposition of Johnny Cash the saint with Johnny Cash the sinner. This juxtaposition is also hinted at in the video through the images of the crucifixion and descent of the heavenly dove. In the pages of the biography, we read of a rising young musician who is enthralled by the Scriptures, yet at the same time cannot avoid the allure of illicit and forbidden relationships. We read of a middle-aged country music superstar who seeks to use his fame and fortune for higher purposes by singing at Billy Graham crusades, even if he sometimes ends up taking to the platform strung-out on pills. We read of a man who courageously stands up for the underdog and the oppressed, singing the songs of the prisoner, the share-cropper, and the American Indian, but at the same time is capable of acting in the most selfish and vindictive of ways towards those closest to him.  This juxtaposition of saint and sinner is neatly captured on the album cover of American Recordings, the album which re-vitalized Cash’s flagging career when it was released in 1994. On the cover, Cash is depicted as standing in the Australian wilderness, dressed in a full-length preacher’s coat, holding his guitar case with two dogs at his side. Reflecting back on the photo shoot, the album’s producer Rick Rubin recalled that the intention was simply to shoot Cash with his guitar, but then the dogs appeared on the scene. Rubin notes, “The whole thing about the dogs was an accident. John thought it was great – the fact that one was black and one was white. To him, it was the idea of sin and redemption.”2

This juxtaposition of saint and sinner is neatly captured on the album cover of American Recordings, the album which re-vitalized Cash’s flagging career when it was released in 1994. On the cover, Cash is depicted as standing in the Australian wilderness, dressed in a full-length preacher’s coat, holding his guitar case with two dogs at his side. Reflecting back on the photo shoot, the album’s producer Rick Rubin recalled that the intention was simply to shoot Cash with his guitar, but then the dogs appeared on the scene. Rubin notes, “The whole thing about the dogs was an accident. John thought it was great – the fact that one was black and one was white. To him, it was the idea of sin and redemption.”2

We see this dynamic of saint and sinner – this history of sin and redemption played out on a corporate level in the life of the church. The church is the community entrusted with holding fast to the teaching and practices associated with the Good News of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. In numerous places the apostle Paul speaks about “handing on” to the congregations under his care what he himself had received, referring amongst other things, to the practice of the Lord’s Supper and to the teaching and proper proclamation of the Gospel (1 Corinthians 11:23, 15:1-5; 1 Thessalonians 2:13; 2 Timothy 1:13-14). However, if the church is to walk in accordance with its missional calling it must not simply be holding fast to what it has received, it must also be actively involved in “handing on” the faith that was once for all entrusted to the saints. It is at this point that we encounter a lexical curiosity, for the Greek word for “handing on” – paradidomi – can also mean “to hand over” or “to betray.”3 This usage appears throughout the Gospels and includes Jesus’ repeated predictions to his disciples that he will be “handed over” to be crucified. Perhaps there is something providential in this range of meanings associated with the word paradidomi, for as the church attempts through its life and proclamation to “hand Jesus on” like Paul, it seems to inevitably “hand Jesus over” like Judas.4 The harder we try to get church right, the more desperately we seem to get it wrong. As we strive to live as disciples of Christ, we find that we actually are able to live like disciples, or at least as the disciples are depicted in the Gospels – confused and scared, betraying, denying, and abandoning the One who has called us to follow Him. We could even venture to say that the church is composed of those who regularly betray Christ with a kiss.

This is the painful truth, but it’s not the whole truth. For by the grace of God, the handing over of the Son of God to be crucified is for the salvation of the world. By the grace of God, the Lord Jesus Christ on the night he was betrayed placed the bread and the cup into the hands of the very disciples who would betray him, deny him, and abandon him, saying, “This is my body given for you . . . This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you” (Luke 22:19-20). By the grace of God, the One who was abandoned by his friends and left to die, rejected and alone, rose on the third day and appeared to those who had deserted him, saying, “Peace be with you” (John 20:19). By the grace of God, our Lord Jesus Christ took a harlot to be his wife, and having washed her with water and the Word, he clothed her in the white robe of his righteousness.

Picking up on this New Testament bridal imagery the great Protestant Reformer, Martin Luther introduced the concept of the “blessed” or “happy exchange” as a way to describe how we who are sinners are made righteous in Christ. In marriage, the bride and the bridegroom are joined as one and share everything in common. Luther writes, “Christ is full of grace, life, and salvation. The soul is full of sins, death, and damnation. Now let faith come between them and sins, death and damnation will be Christ’s, while grace, life, and salvation will be the soul’s; for if Christ is the bridegroom, he must take upon himself the things which are his bride’s and bestow upon her the things that are his.”5 Signs of this “happy exchange” are scattered throughout the New Testament, but the prime example is perhaps found in a passage in 2 Corinthians, where Paul writes:

“So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation: that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us. So we are ambassadors for Christ, since God is making his appeal through us; we entreat you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (5:17-21 NRSV).

This is surely one of the most important passages in the New Testament and we could profitably spend the rest of this evening, or this entire season of Lent, or even the rest of our lives dwelling upon the great mystery and majesty of redemption as it is presented to us in this passage. In our remaining time together I want to draw attention to one particular dimension of this passage that involves the juxtaposition of the indicative, “God has reconciled us to himself through Christ” with the imperative, “Be reconciled to God.” What on earth could Paul mean when he implores his audience to “be reconciled to God?” It cannot mean that we must reconcile ourselves to God by atoning for our sins in some way, for not only is this something that we are unable to do, God himself has in fact already done it. Therefore the command to be reconciled to God must have something to do with acknowledging the justice of God through which God claims his enemies as his friends. Of course, the justice of God is not some abstract principle, ideal or force. The justice of God has a name and that name is Jesus Christ.

It is at this point that the Pauline exhortation “Be reconciled” can be fruitfully illuminated as it is brought into proximity with the Johannine imperative to “walk in the light” (1John 1:7). Being reconciled to the God who has already reconciled himself to us in Jesus Christ must be something akin to allowing the truth of Jesus Christ to shine in an unobstructed way into our lives. The small community I am a part of here at Good Shepherd has been studying 1 John with the help of a wonderful book by Reuben Welch entitled We Really Do Need Each Other. Welch has an uncanny ability to employ metaphors in such a way that they open new vistas into the biblical text. His comments on “walking in the light” are particularly helpful. Welch writes:

“The best way I know to think about that is God shines in Jesus and when I am walking in the light I am walking with the roof of my life open to the shining of God. I understand that kind of mental image – to walk in the light means to take the roof off, open up the ceiling and let the Son shine in. Now that is the opposite of defining, hiding, pretending, those are the covers – to walk in the light is to take the covers off. It means exposing my life to the verdict of God. . . . Our salvation is not in deceit or cover-up or hiddenness of our real situation. It is in the truth of the God who is light. The light that reveals is the light that cleanses and heals – like opening up the wounds of our life to the sunshine of God’s love. The opening of life to God, to his judgment, that is where we are saved.”6

In the light of Christ, we are enabled to see ourselves as we truly are: frail creatures of flesh who have been graciously appointed to eternal life; godless sinners who have been claimed by God as his beloved children. Because our sins have been swallowed up in the boundless depths of God’s love, we can face the truth of our frailty and failures without that truth destroying us. In fact, the saintliness of Christ’s people appears to consist in their very willingness to own up to their sinfulness. It is here that we are in position to appreciate the peculiar saintliness of a man like Johnny Cash, who throughout his life seemed to be only hanging on by his fingertips to the God who had taken hold of him. The saintliness of Johnny Cash is found in his vulnerability to the truth and his willingness to fall to his knees with the tax-collector, crying, “God, have mercy on me, a sinner” (Luke 18:13). A similar saintliness was on display in the life of Martin Luther. Two days before his death Luther wrote a letter that would end up being his last piece of writing. The final words penned by Luther serve as a fitting epigraph to the life of this peculiar saint. Switching from the Latin in which the letter was written into German, Luther wrote, “We are beggars.” Then, returning to Latin once more, he concluded, “This is true.”7

Tonight we have assembled for the purpose of acknowledging this truth. We are beggars. This is true. We will face this truth in a moment as we confess our sins and then come forward to have ashes smeared on our foreheads as we are told that we are going to die. We are beggars. This is true. But the evening won’t end there. Having been marked with the dust to which we shall return, we will then gather around the Table, where our Lord delights to place in the empty hands of beggars the bread of eternal life. We are beggars, but we are also beloved. So as we continue this evening in this time of fasting and feasting, “Let us therefore come boldly unto the throne of grace, that we may obtain mercy, and find grace to help in our time of need” (Hebrews 4:16 KJV). For we are beggars. This is most certainly true.

- Robert Hilburn, Johnny Cash: The Life (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013). ↩

- Ibid., 554. ↩

- A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Christian Literature, 3rd ed., ed. Frederick William Danker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), s.v. paradidwmi, 761-763. ↩

- Christopher Morse draws attention to how “‘Tradition’ in the New Testament contexts either may be apostolic, gospel-conveying, or it may be Judas-like, and a betrayal of the gospel.” Christopher Morse, Not Every Spirit: A Dogmatics of Christian Disbelief (Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 1994), 47-48. ↩

- Martin Luther, “The Freedom of a Christian (1520),” trans. W.A. Lambert, in Career of the Reformer: I, ed. Harold J. Grimm, Luther’s Works, ed. Helmut T. Lehmann (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1957), 351. ↩

- Reuben Welch, We Really Do Need Each Other (Nashville: Impact Books, 1973), 56, 57-58 (formatting altered). ↩

- Martin Luther, “The Last Written Words of Luther: Holy Ponderings of the Reverend Father Doctor Martin Luther (16 February 1546),” trans. James A. Kellerman, accessed January 16, 2015, http://www.iclnet.org/pub/resources/text/wittenberg/luther/beggars.txt. ↩

One thought on ““We Are Beggars”: An Ash Wednesday Sermon”